“All this they did with simple kindness, talking to their guests and making them welcome, without the slightest idea that they were anything but human travelers as poor as themselves,” (Green, p44).

In the Greek mythology that underpins so much of modern western ethics, the wandering man, castaways, strangers and beggars, are sacred to the gods (and may even be gods incognito). Therefore, we should share what little we have with them, our food, our water, our homes. This moral guidance is not unique to the west or to the ancient Greeks, but it does contradict that other common bit of advice children increasingly receive, “don’t talk to strangers”. And it throws into stark itchy relief the images and stories of our actual behaviors towards immigrants trapped on barely viable boats in the Adriatic, children separated from their parents and locked in industrial cages in Texas, or the elderly man begging amongst stopped cars at an intersection in Boston.

I wonder why we struggle with it so much, why these “others” create such countervailing fear in us, that rather than welcoming them in, giving them shelter and treating them with honor, we revile, dehumanize, or ignore them. Is it that we have bought so deeply into the myth of scarcity — do they truly threaten our access to sufficient resources? Is it that we have bought so deeply into the myth of man’s violent nature — will they truly turn on us and attack us? Is it that advances in transportation and commercial hospitality have made the material need for such a moral principle defunct — do we truly think that just because people don’t have to walk for days across landscapes void of hotels to get somewhere, they no longer might need to be welcomed with unpurchased, genuine kindness to a new place? Is it that we are just psychologically overwhelmed by the numbers of those in need — can our brains truly not handle so much empathy?

Suze Orman, popular financial planning guru, says “generosity is when you give the right thing to the right person at the right time — and it benefits both of you,” (Orman, p50). At first blush, it might seem like she is advocating for a conditional kind of generosity, one in which the giver must reap benefits from his gift. But as she elaborates further, she makes it clear that “a true gift has no expectations on it or demands,” (p51) — whole bodies of anthropological literature would suggest otherwise, but let’s go with Orman’s ideal here for a bit. Her argument generally is that generosity should not be an obligation, burden, or harm to the person offering it (or the person receiving). Generosity should be given freely and in a way that enhances or makes the giver feel good about the gifts they are giving, and the receiver feel good about the gifts they are receiving.

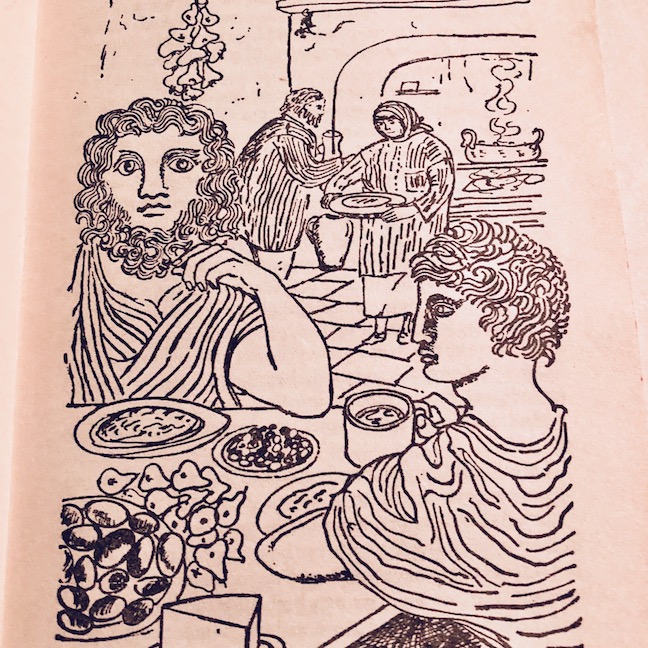

I wonder if Orman would have advised Philemon and Baucis to hold back some of their generosity from their disguised visitors, Zeus and Hermes? In the telling of their story, Philemon and Baucis seem to give everything they have to their visitors — their last bundle of sticks for a fire, their last joint of smoked bacon, their only bed, their store of dried figs, nuts and dates. But perhaps giving everything they had to these strangers in that moment was not the burden it might seem. Perhaps, in their view, these were things they could afford, “poor though they were” (Green, p42), to give away. Perhaps they saw abundance in their world and therefore, giving their “last” was not in fact a burden, because they believed that with little effort they could gather and replenish their stocks sufficiently to sustain them. Perhaps they believed they could trust strangers generally, and these in particular, not to rob, assault or otherwise abuse their generosity. Perhaps they saw a timely need they could fulfill without feeling a reciprocal need to charge for the service. Perhaps they understood that their generosity would have an impact on the lives of two others, and that was enough to make them feel good about their gifts.

When Zeus and Hermes came down that time disguised as travers, they took a survey of three households. Only one of the households treated them poorly, and still Zeus decided to flood the earth and bring doom upon all the wicked. The key virtue in the other two households (that led to the good being spared during the flood) was their generosity towards the two visiting strangers. One could interpret from Orman’s discussion of how we should understand generosity that we have come to incorrectly view it as something expressed out of pity for others or out of a desire to bring others into our debt. These in some ways are selfish, self-reflexive or even narcissistic interpretations of generosity. Perhaps it is this misunderstanding of generosity that leaves us so internally conflicted about how and when to apply generosity to immigrants, refugees, and other strangers and wanderers in our midst. Perhaps it is this misunderstanding of generosity that has led to a world where we build cities that let floods destroy households indiscriminately.

But it is more than just a misunderstanding of generosity at issue here: we also need to come up with coherent and sensible understandings of the key components involved in defining what constitutes the ‘right thing to the right person at the right time’. If we live in a world threatened constantly by false perceptions of scarcity, how will we ever feel we can afford generosity? If we live in a world threatened constantly by false perceptions of mankind’s inherently violent and degenerate nature, how we will ever feel a stranger might be deserving of our generosity? If we live in a world where hospitality is something you can only purchase, how will we ever feel the need to offer it freely and without expectation of something in return? If we live in a world that makes billions of dollars a year from media that fills our brains with images of human-crisis porn from the corners of the earth, how will we ever feel the capacity to share our bounty with those who might benefit from it and know that even thought it might be small, it still makes a difference?

Obviously many of us express our generosity in myriad ways, including welcoming strangers into our countries, homes and lives. But it still feels like so many of the current political crisis hinge around our collective capacity or lack of capacity, at the nation-state level, for generosity, for showing kindness to strangers. As we begin to increasingly work globally and hyper-locally to address issues of ecological, social and economic sustainability and resilience, this leaves me wondering if we also have to reconsider and transform our cultural understandings of sufficiency, human nature, and human needs, as well as generosity and our measures of worth and impact.

Illustration:

by Betty Middleton-Sandford (Green p43)

References:

Green, Roger Lancelyn. Tales of The Greek Heroes. New York: Puffin Books, 1985 reprint of 1958 original.

Orman, Suze. Women and Money. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2007.